Catalog

Texts

Exhitions

Gallery

About Néstor Saiace`s painting

Essay on painting the mystery

by Federico García Romeu

Es un rectángulo tan sólo

entre la geometría asediada del mundo.

Es un rectángulo de espera

al que todo sin embargo ha llegado.

Roberto Juarroz.

Corre fra noi l`angelo.

Porta la forma

come buona novella.

Giancarlo Consonni.

I – INTRODUCTION

Néstor Saiace was a disciple of masters Demetrio Urruchúa, Juan Battle Planas and Julio Barragán, but it is with the last one with whom he set up the closest artistic and personal relationship. Starting from the lessons of these great names of Argentine painting and in a dialogue with the work of his predecessors and contemporaries, Saiace has built and developed an extremely personal painting. Now, a quarter of a century after his first one man exhibition at the Van Riel Art Gallery and sustained by a retrospective view, we can question ourselves on the general characteristics of this work, its tendencies and its significance.

The following reflections are the outcome of a long scrutiny on this work so rich in suggestions-often accompanied by an inquisition on its echoes. Other looks and other reflections are possible; we would feel satisfied if these pages helped to encourage them.

II – HISTORY INSIDE OUT

Nada, nada queda en tu casa natal,

sólo telarañas que teje el yuyal …

“Nada“ (Tango de J. Dames y H.Sanguinetti)

When Saiace’s painting reaches maturity, it is probably the most dramatic period in the history of Argentina, a period leaving an unfortunate balance: thirty thousand missing people, a state swallowed by its armed factions and the loss of an international war. Cultural, economical and educational crises, as well. In short, the identity crisis of the twenties has turned into one of hope. In 1976, little remains of the country the men of Caseros and of the generation of the eighties believed they were founding; even less of the country heralded at the Centennial celebrations: the time of the enthusiastic building has been left behind and it is now the time for a destructive fury. The dream of creating a new and glorious power, melting pot of the different people brought in by immigration, – that paradigm sung in dithyrambic verse by Rubén Darío in 1910 -remained definitely drowned in blood in the seventies. There were few who did not feel the burden of the long chain of frustrations and disappointments, the emptiness of voluntaristic speeches, the load of a hideous history entering by effraction into the amenities of a made up history.

It is difficult and it maybe even unjustified, to bind the events of a creator’s life to his work; but it is useful to keep them in mind, as a back drop, because every work breathes with the echoes of its time. In Saiace’s painting the rages of contemporary Argentine appear in negative, they are an “unsaid”. In opposition to the noisy convulsions of everyday history lived by Argentinians during the seventies, this painting seems to be harbouring in a deep silence, in a profound insight, to assert the right of abstracting to rebuild a human world from color and form.

III – SAIACE’S PAINTING AS A MYTHICAL TRANSFORMATION OF REALITY

Clarificada azul, la bora

lavadamente se disuelve

en la atmósfera que envuelve,

define el cuadro y lo evapora.

Rafael Alberti.

L’homme possède un certain regard qui le fait

disparaître; lui et tout le reste, êtres, terre,

et le ciel, et qui se fixe, un temps bors du temps.

Paul Valéry

The first thing that strikes in Saiace’s painting is its mysterious character, the observer’s impression that the work refers to an enigmatic universe. The scenes depicted belong to everyday life -interiors or exteriors of cafes with their patrons, dancing groups, orchestras, circus scenes- but we discover a weird atmosphere in them: the human figures seem celebrants of a ceremony, actually not living the accomplished action but another one of a higher significance. Why? Perhaps because Saiace’s painting is a painting of immobility: apparently settled in a world where movement had been naturally excluded and form had reached a definite stillness. Moreover, in painting his characters, Saiace has omitted specific references to treat them only by way of the complex color relations displayed on the canvas.

Saiace’s painting would appear to have two contexts: one, which we would call literary, would include what can be told about the referential event and another one which would be purely pictorial. The first context is void, it promises to say something but fails to do so, and leaves, quite openly, room for displaying a pictorial meaning. This relationship between an empty although present text, and a full text, this semi-abstraction forever in an unstable balance, may be another reason for the observer’s impression that he is approaching a naturally essential event, deprived of any anecdote, whose definite protagonist may be an immutable time in which the characters are trapped as if in a spider’s web and dissolved in it. Lights vary, bright or gloomy, the palette is either warm or cold, but the pictorial construction ends in an unrealistic transformation of the light, the space and the characters dwelling there. This transformation, achieved by transposing the real and contingent to a world in which every feature of the singular form is annulled, shows something of a mythical transformation.

Saiace transcribes man’s everyday time into mythical time and his body into a timeless substance. It is the saga of a transubstantiation via the values of its pictorial matter. The figure becomes a figure of figures, a flat abstraction on a background only apparently little differentiated; it seems to be living for itself, in a definitive time, the history of all changes. The work appears as a “rectangle of waiting, where everything, however, has arrived”, an Annunciation “as good tidings” of the world of forms.

When slightly lifting the veil that hides it from our sight, Saiace exhibits an archetypal and nostalgic world only intuitively approachable. The encounter is an instant of communion with what we might call the absolute, or what we might be able to guess about it.

IV – COMING UPON A NAME

Efforçons-nous toutefois de poursuivre notre

chemin, fût-ce à vent contraire, de notre pas

lent. Mais sans renoncer à l’obstination de

gratter notre petite allumette, pour faire un

peu de lumière. Tant que durent les allumettes.

Antonio Tabucchi.

Saiace’s painting of the first years of the decade of the seventies was named as expressionist by some critics and fauve by others. But as we shall see, very soon this painting abandons the cannons of such movement. Loyal to Tabucchi’s invitation in the above quotation, Saiace followed his own way, a bit lonely, and enlightened it with his effort to build a coherent work. Fauvism and Expressionism, in their time, were important advances in the renewal of painting and in the final ruin of the representative system inherited from the Renaissance. They increased the distance from academic painting started by the impressionists and contributed decisively to the out come of a new way of looking. It was a at liberating moment for painting. But the founders, excepting a minority, did not stop in the middle of the road: once the new way of treating color and space was acquired, they abandoned their exuberant colourism and devoted themselves to the exploration of the consequences of their first contributions.

If by some of its characteristics-arbitrary chromatism, favourite saturated colors and summary treatment of the human figure – a part of Saiace’s early paintings appears related to expressionism or fauvism, very soon the painter’s patient work with matter leads him to look for paths aesthetically distant from that filiation. Thus, the exasperated chromatism of some portraits of the seventies is followed by a painting in which colors become dull and stretch in a vibrant murmur of countless shades; color vibrates, unclamourously, even in the gloomiest shadow.

Possibly the source of the generic treatment of characters already pointed out in Saiace’s paintings springs from his portraits of the so called expressionist period. The painter did not intend to be loyal to the figure of the portrayed but he explored the specific of a certain chromatic configuration: the individual was represented by an arbitrary and unique meeting of colors. But what began as a pictorial research will turn into a definite feature of his language. By this means, Saiace will be able to render what is most humane in humanity, that is, the strictly essential.

If one tries to “translate into poetic form what one can see” the first thing that impresses in Saiace’s work is his lyricism, not the casual chromatic aggressiveness, which, on the other hand, has remained behind. Saiace’s art is one of suggestions and shades, not of commands. Perhaps because nothing is said but everything is suggested, the observer participates in the building of significance, helps with his experience and his memories to fix its sense. What aesthetics can a work like this be related to? Maybe to one akin to Mallarme’s poetic, which intends to express, through words retrieved from their ordinary use, a transcendent reality, alive in and for the poem to which this saves -if only for an instant -from the common wreckage into Nothingness. Thus the poem is a metaphysical entity whose being is shining behind the darkness of an elusive approach. A limpid reality, built, purely rational. In this art, which is all suggestion, naming is explicity avoided, as if in so doing the object became loaded with the weight of all the accidents and overwhelmed in its perishable impurities.

Such is Saiace’s painting: it does not propose a symbolic, emblematic or allegoric representation of reality by means of transcending signs; he offers it to our intuition, apparently free from the objective attachments of the represented specific being.

Perhaps unconsciously replying to a degraded reality, Saiace’s painting places itself above the quarrel in which the real plunges down, on a level which does not deny it but transcends it. How can we call this painting, with what name suggestive of its intimate contents, which we can grasp through its poetical brightness? Perhaps «transrealism» is an adequate name, as good as any other, to express that Saiace’s painting transcends reality, without invalidating it. In other words, that it proposes a transcendent reality.

V – STRIVING AFTER HIS OWN STYLE

Until he conquers the transcendent peace and serenity of his mature work, Saiace is committed to acquire his distinctive pictorial language and full command of the technicalities of his art. It is the span between his beginning at Urruchua’s atelier and the first years of his pictorial connection with Julio Barragán. This last relationship, regarded from the distance, assumes capital importance in connection with what will be Saiace’s personal work.

It would appear that Saiace’s first concern has been to master the opposition and complementation among colors and hues. It is the time of his still lifes (1963) painted with dull colors in harmonizing earths-colors occasionally opposed to cool ones. In these pictures there is a deliberate absence of perspective and light does not come from a directional source but flows from objects (Chianti y Pan, Mesa con Jarra y Berenjena , Pava y Choclo, Mesa Provenzal con Frutera). The choice of earths and lights sent out by the object, often from the center of what is represented, will always be present in the future, in spite of a remarkable enrichment of the palette and of other treatments to come.

“Mesa provenzal con frutera” – Oil on cardboard – 50 x 56 cm – 1963

Saiace’s presence in J.Barragan’s atelier is revealed by an important change in chromatic range and in subject treatment. It is the moment of saturated, bright colors, distributed in patches, with whites and blacks with a color modulating function as in Naturaleza Muerta con Jarrón, (1971). It is as if a dam has broken up and colors now can flow freely. A subsequent series of works served to judge Saiace as an expressionist (Extraterrestre, 1972; Tristeza, 1971; Adolescente, 1973). Ernesto B.Rodriguez saw “the joy of painting” in the pictures of this period. In the above mentioned portraits, the human figure -short of relief- is summarily translated, sketched in thick brush strokes, a treatment parallel to the unrealistic coloring. Here, form becomes a mere pretext to develop color counterpoints, making them look like phantasmagorical apparitions. However, in Retrato I and Retrato II (1972), the figure, superimposed on a dark background, is treated in a more classical way: its expressivity, free from any chromatic exuberance, is stressed by an almost frontal light and the gaze is directed rather to the observer or the painter than to an undefined point as in the expressionist portraits. This period offers a wealth of trials and rapid acquisitions. Saiace’s work is growing in complexitiy as shown by a series of works from 1974 to 1978 (Cabeza con Sombrero I (1974), Cabeza con Sombrero II and Cabeza con Sombrero III (1977), Mujer Sentada I, II, III and V (1976). It is as if the capricious color had found its full expression and its purely pictorial motive -and not a justification for the sake of the search itself – by means of wisely shaded contrasts, complex harmonies and transparencies; the earlier chromatic apposition seems distant, even being so recent. But within that same span (1974 – 1976), works that go further on and anticipate the future ones, are being born like Russian dolls as in 1972, for example Jarrón con Flores (1974) and Autorretrato (1975). The rich palette and volume expressed by color and lightness of the brush, impress as pure painting of liberated as well as liberating works for the creator. The loose and convincing graphism of Mujer Sentada I (1976) will later appear under different forms, less evident though equally free.

“Retrato II” – Oil on hardboard – 50 x 60 cm – 1972

Since 1977 Saiace’s painting appears fully developed and his authorship is recognised at first sight. In Café Nocturno (1977), winner of the Sadao Ando Prize at the LXVI National Salon, 1977, his style is definitely constituted. Here we sense the vibration of darkness, the poetry of the night. A careful rhythm of light sources dispels the darkness without altering it; conversely, it is deepened by contrast. In the picture we are now commenting Saiace obtains lights which seem to come out of the characters themselves or out of some object. Figures without volume -there is no real chiaroscuro, only chromatic distances-planes that create by their abstraction a strong impression of unreality and add to the enigmatic atmosphere of the picture.

“Café Nocturno” – Oil on canvas – 80 x 130 cm – 1977

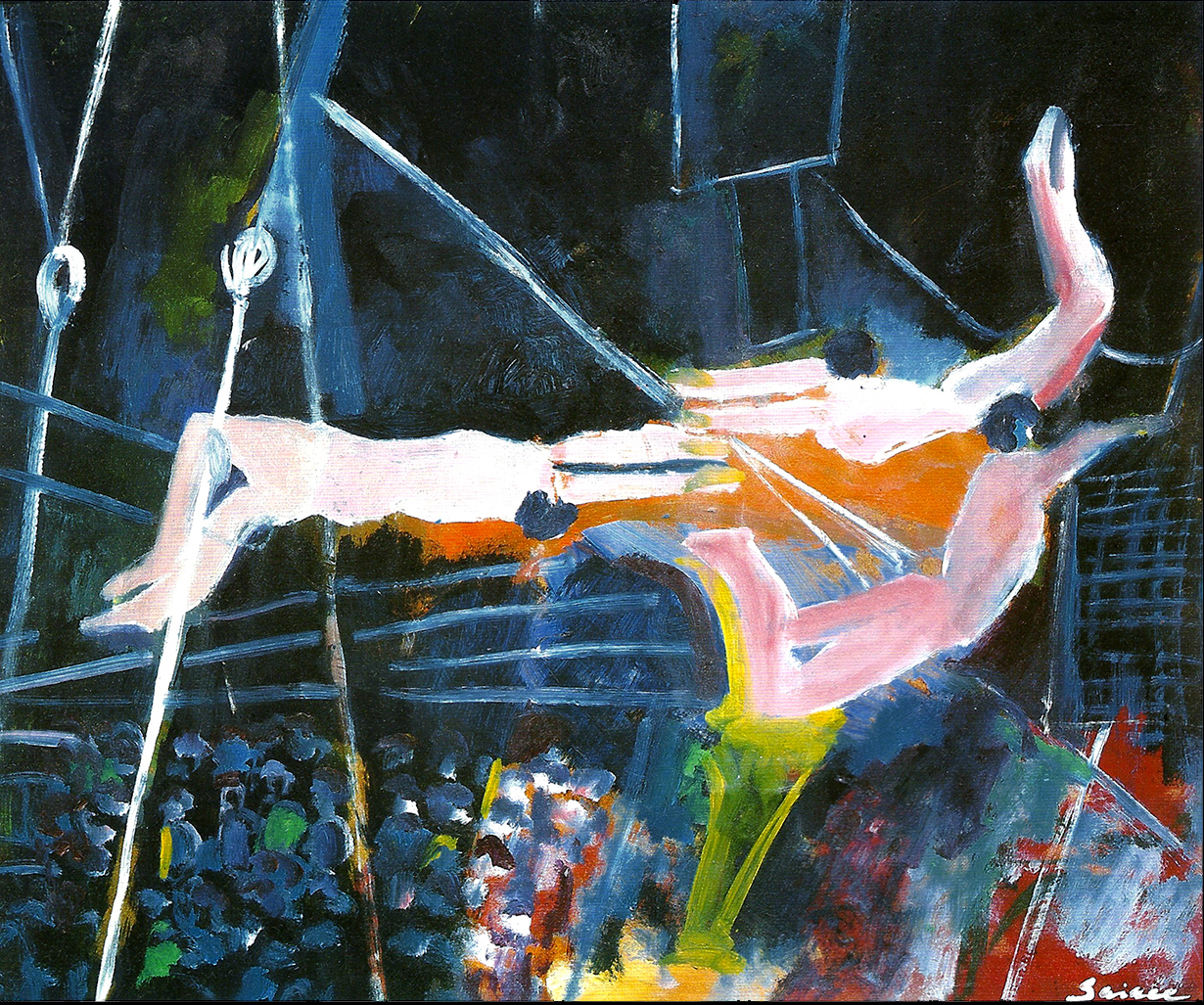

With the Circus series of 1990 Saiace achieves the culmination of his work, displaying all of his poetry. The core figures-acrobats, horse-riders, trapeze artists-exhale light against a background of deep, warm and cool colors, made up by the circus tent and the mass of individually slightly sketched spectators. In spite of Saiace’s resorting to bright, saturated colors only in some pictures of this series, they all impress as facing flames and hot coal; the circus scene turns into a fire in which the characters -disjointed or better still, boneless- are burning.

“El Circo IV” – Oil on hardboard – 50 x 60 cm – 1992

Though the nocturnal atmospheres and dull colors are frequent in Saiace’s works, the more or less cyclic alternation of pictures of luminous colors seems to introduce an allegro rhythm, a song that springs from the very depths of the picture. As spring and autumn, as winter and summer, it accompanies the days of dream and of awakening through the passion for color.

VI – SAIACE’S THEMES

Sobre la escena ya desconchada

por el otoño que el flautín

une su pena de madrugada

su nota oblicua con el violín,

y la pareja danza enmarcada por la

inminencia de puñalada

que es la frontera del cafetín.

Nicolás Olivari.

Although the motives of Saiace’s painting are intimately bound to legendary Buenos Aires themes -like the tango ones, through typical orchestras and dances, or those of the cafes -the vision it expresses, frequently crepuscular, is intimate, timeless, short of documentary aims. But besides, in his mature period, this work illustrates almost always a world of men and women representing a convivial theater -chatting, dancing, making music- illustrating sociability and allegiance to man among men, Saiace’s painting often puts on the stage luminous beings surrounded by the darkness of the world.

In the mythology of Buenos Aires, the “café” and the bar -at times with a typical orchestra- are microcosms, theaters of life, meeting places of hopes and disappointments, at times stages of what cannot be remedied, of the fulfillment of a destiny, of final events: the final cafe, the final hangover sang by innumerable variations of the tango. In the dim atmosphere of the Buenos Aires bistros, sheltered from an already chaotic outside, perhaps as void and hostile as in the tango “Mi Taza de Café”, characters created by Discépolo come to life; they are -as inspiring sources of an almost hermetic teaching- the figures of “José and his chimera” or of “Marcial, who still believes and hopes”, the shadow of “Abel, the skinny, who left us but is still guiding us”. How many José, how many Marcial and Abel are surviving in the bars and cafes of Buenos Aires, chatting about everything and about nothing at all, refugees of a chaotic country, to talk “about the facts of life” or “to wait for the show to end”? We have all seen the character of “La última curda” leaning against the tin counter holding a glass of wine in his hand and a lighted cigarette on his lips, looking far into an unreachable distance, at a time and in a place which no longer seem to be ours.

In the series that Saiace devotes to “cafés” the multiple meanings of this central place of “porteño” mythology are unified. Their patrons, almost unreal and liberated from the anecdotal, seem to be on the other side of destiny. The “café” -because of this process of dedifferentiation from reality proper to this painting- turns into a place of transcendence, both inside and outside the world, an arrival after a passage through the contingent.

The inspiration of the “cafés” is drawn from Buenos Aires, but because of the effect of abstraction of this painting, they may be located in any of the “cities of the world”. In this series, there appears, in fact, the occasional Parisian café, as the “Deux Magots” or of other cities in which the title of the picture is the only sign of recognition. Let us add that scenes of other cities bear a special meaning: they were conceived during a spring tour on Europe, a deep breath of fresh air after the heavy closure of the military dictatorship.

Saiace gives life to the tango in his work, or rather to the tango back ground veiled by his creative-of-mystery look. He often returns to painting small instrumental groups, not all of them precisely “typical orchestras”, but resembling them. Because in them one can feel the hidden Buenos Aires, the complaint of the bandoneons, perhaps the soul -or something else for agnostics -of the great city. In his popular dances, as well as in his cafés, the mythical city displays its enigmatic presence. Saiace is its painter, the painter of a timeless universe rooted on the banks of that “river of drowsiness and mud” which Borges told us about.

VII – TO END UP, LET’S SAY THAT…

The above is an essay, one among the many possible ones, on the analysis of Saiace’s painting. The reader can expand, enrich or correct it. Maybe at the end of his journey, he will share our own conclusions: Saiace’s work exhales a mystery that is not exhausted by the commentaries it inspires. It is as well for mysteries to remain such. Which reminds us of that dialogue between Mairena and Rodríguez[1], his disciple:

M – And can you see clearly what you are saying?

R – With a perfectly obscure clarity, dear master.

Federico García Romeu

[1]- “Juan de Mairena“, 1936, Antonio Machado.

• next –>