Catalog

Texts

Exhitions

Gallery

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTICE

I- CHILDHOOD OF A BOY IN THE TWENTIES

Néstor Virgilio Saiace (1923 – 2014) was born in the Buenos Aires, quarter of Almagro, of an Italian immigrant family formed by Angela Cerboni and Gregorio Saiace. They lived there all their life in Boedo, Treinta y tres, Yapeyú and Castro Barros streets -frequently moving house because of economic difliculties-.

Gregorio was a shoemaker; he was born in Tropea (Calabria), a small fishing port on the gulf of Saint Euphemia. Besides Néstor, the couple had a daughter, Diana Tea, the elder and another son, Florinio Silvio Sol, the youngest. Names of strange echoes were frequent in the first years of the century, coinciding with the broad diffusion of the anarchist ideals that prevailed among us. Libertarians -and Néstor’s father was one of them- had replaced the calendar of saint’s days by another in which liberations and redemptions were evoked, as well as astral bodies, natural phenomena, the 1793 Republican Calendar and even literary pieces. It was the time of Libertad, Liber, Luz, Sol, Helios, Floreal, Fraternal, Redento, Germinal, Armonía. These fancies ended up by upsetting the very conservative Argentine administration which, after 1917, witnessed the arrival of several Trotskys and Lenins in swaddling clothes; excited and uneasy about the future, they decided shortly after to forbid the inscription of names not included in the calendar of saints’ days. Those were, as well, the times of the “Patriotic League” and the “Traditionalist Revolution” in which the “defenders of the nation” shouted against the “dissolving ideologies” introduced by immigrants. Lugones in “El Payador”[1] speaks about the “ultramarine plebeians who, like ungrateful beggars, make fuss in the hallway” -and invented, from the beginning to the end, a bucolic “gauchesca” of a definite decorative sense in which they installed the true national essence. For the frightened heirs of those who had made a pariah of the gaucho Martín Fierro, the immigrants were the scapegoat for all the difficulties of the country. The prosperity achieved by some descendants of those families who settled down to “make their America”, makes us forget that for many of them life was difficult in that period of identity crisis and nationalistic reaction. The economic commotion of nineteen twenty-nine only made things worse.

The development of those libertarian organizations in our country -so important until the decade of the twenties- was closely linked to Italian immigration, made up mostly of landless farmers and artisans. Saiace recalls in some biographical notes that his father’s anarchist ideals were over and above the domestic material needs; although Gregorio does not seem to have been an activist of the anarchist cause -briefly “the cause”- he was always in trouble to keep a regular job because of his libertarian conception of existence and his little regard for the submission of workers to owners. His mother’s job at the sewing machine at home was not enough to make both ends meet. That is, poverty was everyday’s bread.

The 1929 crisis blew a hard stroke to the Family, which in 1931 was evicted for not paying the rent. Saiace recalls that as he was running out of breath to his aunt’s house to break her the sad news and beg her some money, he was thinking what he should do to avoid a similar situation in the future. It is perhaps this memory that prompted his picture El Desalojo (Evicted), painted in 1980, whose desolate protagonists seem to be waiting for an answer never to come.

The eight-year old boy must have been deeply perturbed by the family’s wreckage; it is no doubt due to this that he started working before he was ten years old, before and after school hours, from 7 to 12 in the morning and from 17 to 20 at the evening. His first job was as an errand boy in the municipal market of the quarter; he later held the same job in a butcher’s next to the market -an important issue for his future, because there he met Jacobo Muchnik and through him he entered the Compañía General Fabril Financiera.

El desalojo – óleo sobre tela – 60 x 80 cm – 1980

II – FABRIL FINANCIERA, THE GRAPHIC ARTS AND THE GROWTH OF A FAMILY

Fabril, with over two-thousand workers, was the most important printing establishment in South America and Jacobo Muchnik (1907-1995) -the advertising manager- an outstanding man. Born of immigrant parents from Eastern Europe, a man of a culture rooted on the ideal of a democratic, just and generous Argentina, as the republican school had taught him, used to define himself as a civilizer. María Teresa León said of him that he had invented his own life. There is not a better example of this invention than how, in the middle of the crisis and the rampant unemployment, he worked his way in Fabril creating his own position [2], in April of 1933, he reported to Pablo Paoppi, Director of the Company’s graphic workshops, and after delivering a speech about advertising and its importance, he announced that he was not after a salary. He would rather have a percentage over the advertising jobs he might bring in and a place where to lay his belongings down. The Director agreed on the trial and shortly afterwards Muchnik ruled over several employees and managed an activity in permanent expansion over the following thirty years.

Jacobo Muchnik used to tell that one day the butcher’s delivery boy, who was about to finish his primary school and was a friend of Jacobo’s son, had reported to him to say that he wanted to work for him. Muchnik was fond of enterprising people wishing to advance in life. On the other hand, as he was capable of holding passionate conversations with everybody, young or old, educated or illiterate very likely he enjoyed a long talk with this 14 year old adolescent who so spontaneously had approached him. So in 1937 Saiace began to work as an office boy in the Advertising Department of Fabril Financiera.

In the thirties, the Advertising Department of Fabril gathered outstanding personalities of the Graphic Arts: Valerien Guillard, a graduate from Ulm, Ricardo Escote[3], a Catalonian creator established in Argentina and Alcides Gubellini (Bolonia, 1900 – Buenos Aires, 1957), an Italian painter whose exquisite sensitivity appears in his famous and delicate paintings (today in important private collections) and in his terracotta figures. Close to them, as a very young man, Saiace begins an activity which he will keep learning about during all his life and which is at the root of his pictorial calling and of his knowledge of color: graphic arts.

In 1942, Saiace leaves Fabril to enter “F. G. Profumo y Hno.”, one of the best among the top fine printing shops of the city. Military service forces a pause in his career but once it is over, in 1944, he returns to Profumo.

In 1946, he marries Lastenia Clementi, whom he had met in 1940. At the time, she was a secretary to Dr.Hugo Lifezis, a refugee Viennese lawyer, who created “International Editors Co”[*], together with Jacobo Muchnik make an enterprise specializing in copyright (the first one in southamerica). In 1949 when Saiace becomes independent, he leaves “Profumo” and with four partners starts a graphic arts enterprise called “Lesague” which he manages from the beginning and is still managing.

Gabriela Clara, the couple’s first daughter, was born in 1954, and Zaida Hebe, the second one, was born four years later. On the same year Saiace ends his secondary school and reviews his multiple vocations, which end up by cancelling themselves: medicine, architecture, psychology, mathematics… And finally he arrives at a definition of his true vocation: painting.

Néstor Saiace

III – TRAINING FOR THE PLASTIC ARTS

There is something very deep and passionate in Saiace’s relation with his firm: it has been and still is the place of an adventure and a struggle fought with devotion and perseverance. We have already seen his early encounter with the Graphic Arts -his first school of color and graphism- since the end of the decade of the thirties. Then came the setting up of Lesague, his own printing company. This enterprise, which he founded with four partners forty-nine years ago, in which he remained alone since 1965, performed and is still performing, under his constant impulse in search of technical perfection, an outstanding activity in the printing of art works in our country. It is requested by painters anxious to obtain faithful reproductions of their works; a printing shop of art books of refined manufacture and also of numberless artists’s exhibition catalogues. In its impressions, “Lesague” devoted attentive care to obtain a flawless job. Need less to say, this permanent care goes hand in hand with a delicate sense of color and constant loyalty to the reproduction; both qualities have been for Saiace a school of demand towards his own work. Moreover, Lesague has meant for our painter the chance of meeting the greatest names of Argentine plastics, another way of familiarizing with the work and the person of his colleagues.

In 1962, he established close contact with painting: he entered Demetrio Urruchúa’s (Buenos Aires, 1902 – 1978) atelier. He recalls that it was a large rented hall on the first floor of an old house located in Carlos Calvo and Entre Ríos streets, which was reached going up a steep iron staircase. The disciples gathered there on Friday and Saturday evenings to submit the weeks’ production to the master. Each one presented his work on the easel; Urruchúa gazed steadily, meditated for some instants and then commented at length or asked somebody in the audience to speak. His method -Saiace says- was that: talk, ask, suggest, never approve or dismiss. He used to say he could not teach painting or drawing to anybody because these things are connatural, common to all; the master can only awake them, bring them to the light. And he added that only discipline and total devotion on the part of the true artist could surmount his candid stage of innate knowledge to attain the real artistic expression. Urruchúa’s teaching was, therefore, maieutic, leading to the illumination of one’s own way rather than having it traced. He had to resist, at times, tendencies towards monotony; for example, if someone abused of grey colors, he suggested using red and to whom showed an inclination towards flowers, he proposed painting fruits. Everybody started by painting still life. In apparent contradiction to the arbitrary colors of his own palette, he invited his disciples to copy the colors of eggplants, tomatoes, peaches and lemons. “You’ll learn to combine colors -he repeated- because nobody teaches better than Nature itself”. And the disciples learnt, working without theory, with enthusiasm and self confidence. Saiace treasures a kind memory of the master and those years of apprenticeship. He used to tell him to give up printing and devote himself only to painting. Once, after following closely the master’s suggestions, he had to discontinue his lessons; the master prophesied: “He who leaves without being pushed out-of the painting, of course comes back without being called.” And so it was.

Many figurative and non-figurative painters of various trends, sprang from Urruchúa’s atelier, almost all of them owners of a strong pictorial personality. Few masters have known as he did how to display -mediating a pedagogy centered on freedom- the distinctive features of each disciple. And Saiace remembers that his classes included exercises on civic virtues, a tribune against authoritarianism, injustice and falsehood. Because, to him, as he said in his memories[4]: “The authentic character of a work of art originates in the stand the artist takes as a man”.

Juan Battle Planas (Torroella de Mongrí, Spain, 1911, Buenos Aires, 1966), whose atelier Saiace attended, resorted to a totally different method from Urruchúa’s effusive one. Critics ascribe Battle to the surrealist stream; he developed a dreamlike, mysterious work in which he reflected his spirituality, won by Zen buddhism, with great pictorial wisdom. According to Saiace, Battle was interested in the disciple’s interior. The applicant’s interview was an interrogatory like the homeopats’ anamnesis: he wanted to know if he used to dream at night, if the wind bothered him, if he choose cold or warm baths, what food he liked best and which were his dislikes. Battle applied automatism to is painting and that was the starting point to build the image. This method did not agree with Saiace, although he avows that his familiarity with Batlle’s atelier brought him instruments to approach a pictorial reality which he had ignored up to then.

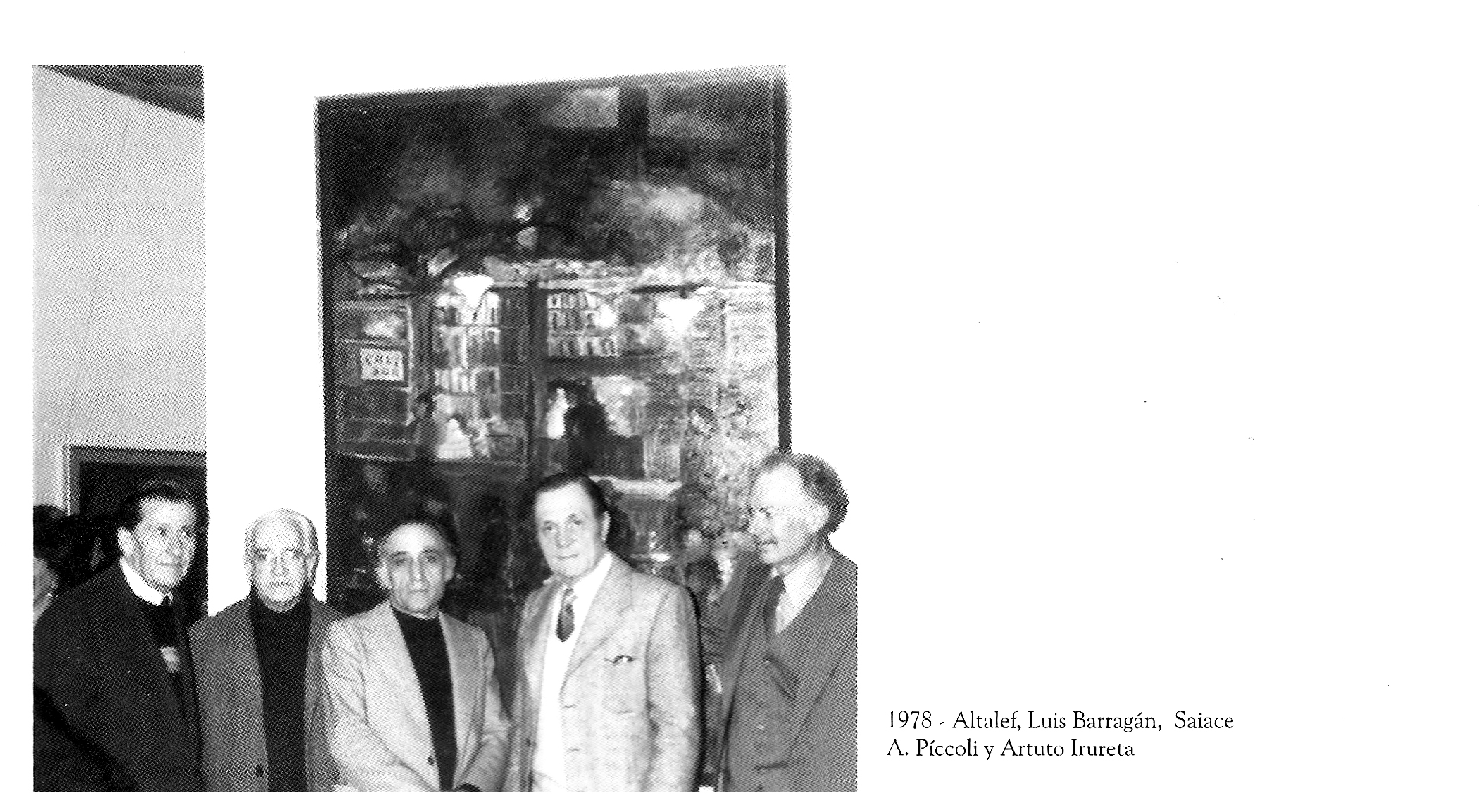

With Urruchúa’s and Batlle Planas’ teachings Saiace frequented two opposite extremes of Argentine painting of those years: one linked to the sensual expression of matter, at times discursive and emphatic and always brightened up by a great expressive strength, while the other one, Batlle’s painting, appears as a mise-en-scene of a phantasmagorical interior world, conveyed by a subtle color treatment. These sources do not appear in Saiace’s painting, but it might be questioned whether they were not incorporated to the matter of the work itself in a synthesis between two apparently disconnected opposites. Perhaps the bridge that allowed Saiace to produce this unexpected synthesis was Julio Barragán’s method. He commands an encyclopedic knowledge of painting and develops his expressive means entirely at ease. By the turn of the decade of the seventies, when he meets Saiace, he is a fully mature painter, whose merits deserved the Great Honor Prize awarded by the National Salón a few years later.

In 1969, Julio Barragán is preparing a one-man exhibition at Wildenstein’s and is looking for someone to print for him a fine catalogue. Don Fernando Arranz, headmaster of the National School of Ceramics, suggests Saiace for the job. Saiace printed the catalogue and from the first encounter with Barragán their relationship grew into a sound friendship. When Saiace showed him what he had painted at Urruchua’s atelier, Barragán told him too that he should devote himself to painting and invited him to paint together. Saiace admits that his real master was Julio Barragán and that their encounter was most important for his formation. According to him, Barragán took his task to heart and his appraisals were always sound and pertinent. Thus, Saiace was able to find his own path. Because Barragán, as well as Urruchúa, more than teaching a technique, accomplished the function of giving birth to Saiace’s rich pictorial personality. Like Urruchúa, he taught him to be himself, which is the supreme teaching a master can dispense. The dialogue between them actually goes on to this day.

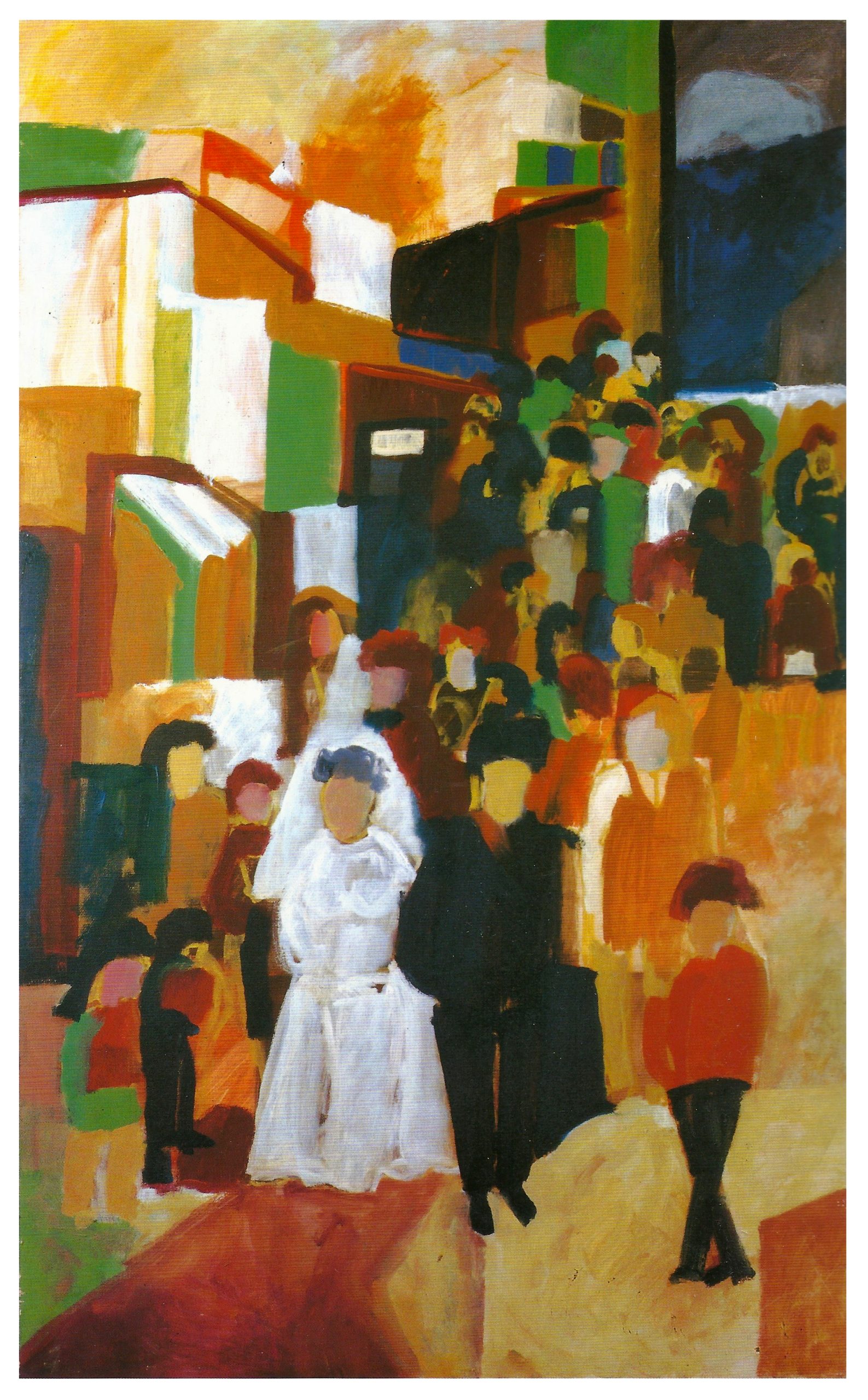

Saiace’s visits to European and North American Museums fill an outstanding place in his artistic formation. He cherishes the memory of the first time he found himself facing a Munch, or a Greco, a Van Gogh or a Gaugin and he enthusiastically describes those moments as so many revelations. The list of pilgrimage sites is a long one, the stations after a painter, a work, a museum are numerous: Madrid, Barcelona, Paris, London, Amsterdan, Otterlo, Oslo, New York… Another excitement: the Mediterranean world, his parents’ own from which he brought us the Casamiento en Tropea de 1977, the world of Ulysses’ and Eneas’ travels, the source of so many perdurable archetypes, that of cities and places where reign uncomparable lights and unfathomable shadows: Rome, Florence, Calabria, Sicily, Athens, Delphi, the islsands… and the land of mystery: Egypt.

Casamiento en Tropea – óleo sobre tela – 130 x 80 cm – 1977

In 1973 he gathers an enthusiastic critique at his first one-man exhibition at Van Riel Gallery. This success repeats itself in the subsequent exhibitions which, through a commendation by maestro Raul Russo, he will release at Wildenstein’s between 1975 and 1990, date of the gallery’s closing up. From 1976 Saiace participated at the National Exhibition of Plastic Arts Salons. He was awarded the Sadao Ando Prize at the LXVI National Exhibition, in 1977.

Saiace’s biographical outline ends here. From his first one-man exhibition at Van Riel Gallery, his work is public and has been judged by art critics and connoisseurs.

[1] – Leopoldo Lugones; El Payadtor, Otero y Cía, Buenos Aires, 1916.

[2] – Jacobo Muchnik; Cuentos sin cuento, Muchnik Editores, Barcelona, 1985.

[3] – Guillard y Escoté dirigieron en su momento la sección “Arte“ del “Departamento Publicitario“ de la “Compañía General Fabril Financiera“.

[4] – Demetrio Urruchúa; Memorias de un pintor, citado por Osiris Chierico en Catálogo de la muestra homenaje, Buenos Aires 1988.

[5] – Mauricio I. Neuman; Julio Barragán, (66 reproducciones en color y 22 en blanco y negro), Ediciones Lesague, Buenos Aires, 1980.

• next –>